Election Year History Belies Ambitious Talk on Appropriations

Lawmakers’ spending goals could run right into midterm hex

November might seem far away, but the midterm elections’ impact on spending bills is already on display, amplified by internal Republican jockeying for leadership positions in the House.

Election years tend to chill swift movement on appropriations bills — especially when there’s potential turnover in leadership of one or both chambers. That’s in part because lawmakers want to focus on campaigning and are back home more than usual, and party leaders tend to want to shield vulnerable members from tough votes.

It’s also because the party out of power has an incentive to withhold support if they believe they can take control the following year and can shape spending measures more to their liking.

Watch: How Do Elections Impact Appropriations?

For instance, in midterm elections going back to the Reagan administration, there has been a change in control in at least one chamber in all but three cycles: 1982, 1990 and 1998. And the party in power has lost either the House, the Senate or both in all four of the most recent midterms going back to 2002, a statistic not lost on Democrats hungrily eyeing the House Speaker’s gavel and possibly the Senate as well.

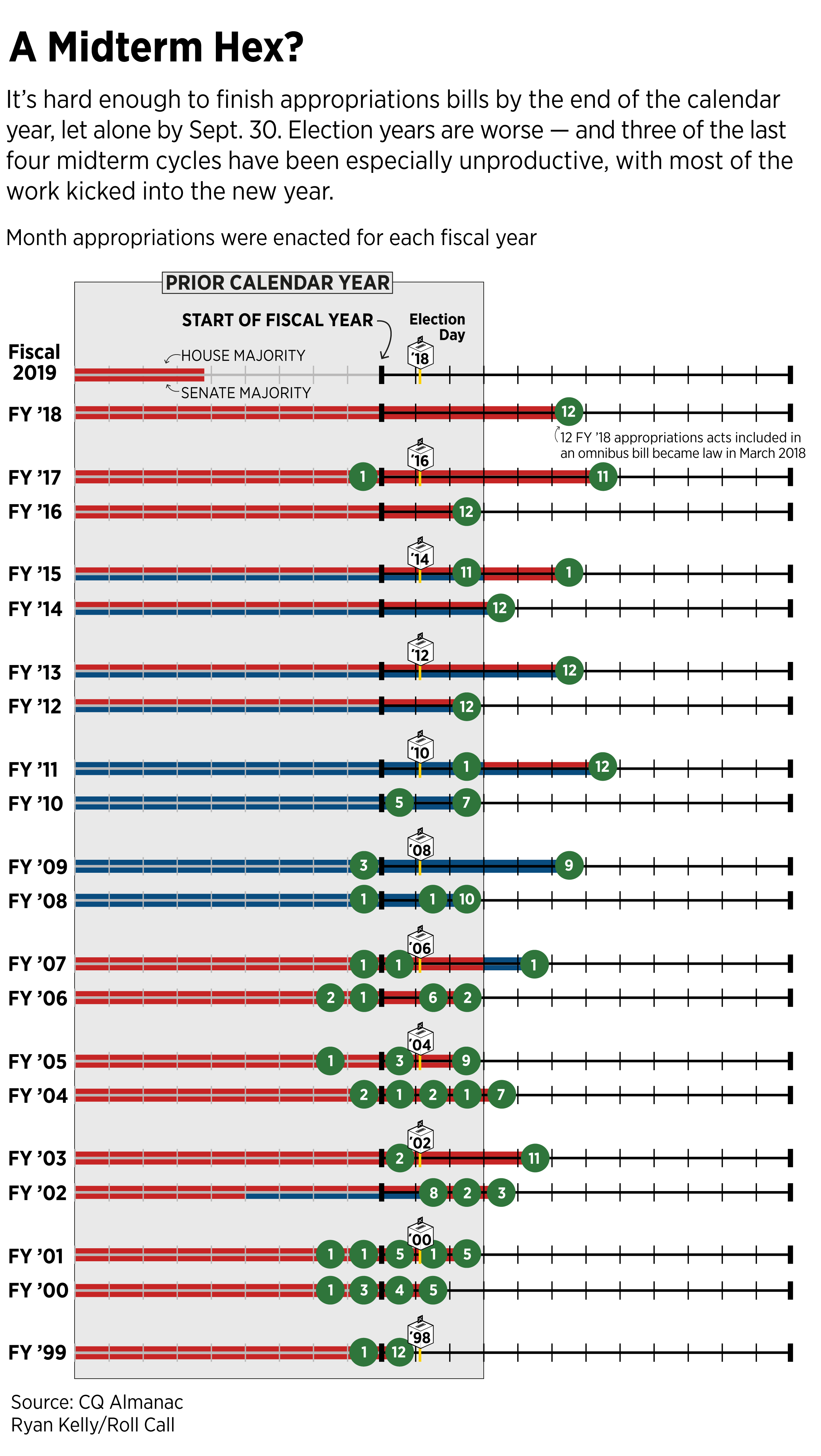

The implications for appropriations have been uneven across the spending cycles, and not completing work on all of the appropriations bills during the calendar year, let alone by the end of the fiscal year on Sept. 30, is common. But especially in recent years, the average output for Congress has been slim during campaign seasons: just two spending bills completed before the end of the calendar year, on average, in election years dating back to 2006, an analysis found.

That’s not always the case, as sometimes the minority party that takes power decides to play ball in the postelection lame-duck session and cooperate on spending bills to clear the decks for the following year’s agenda.

For example, after Senate Republicans took control in the 2014 elections, Congress was still able to complete work on an 11-bill fiscal 2015 omnibus in December, leaving only the Homeland Security bill hanging over until the new year over a GOP dispute with President Barack Obama over immigration policy.

‘Regular order’

Nonetheless, it’s an election-year habit of appropriations leaders to trumpet calls for “regular order” early on, a message already coming out of the House and Senate.

President Donald Trump has ramped up the pressure by vowing on March 23 never to sign legislation like the catchall omnibus spending measure for fiscal 2018 again, suggesting that both the process and the size of the bill were a problem.

“I say to Congress, I will never sign another bill like this again. I’m not going to do it again,” he said. “Nobody read it, it’s only hours old.”

The omnibus was based off spending levels in a two-year budget deal Trump signed in February, which also sets spending increases for fiscal 2019. Overall, discretionary appropriations for fiscal 2019 would increase by $36 billion over the current year, or 3 percent — an extra $18 billion each for defense and nondefense categories.

Extra money on the table will be an incentive for members to enact regular appropriations because individual lawmakers will have more control over spending than with a continuing resolution, which typically extends current-year funding levels.

However, efforts to advance spending bills can often break apart after Appropriations Committee approval when a contentious midterm beckons.

When Republicans took the House in 2010, for example, zero appropriations bills were completed during the calendar year, and a final spending bill didn’t get enacted until April 15, 2011, when fiscal 2011 Defense appropriations were attached to a yearlong continuing resolution. Similarly in 2006, when Democrats took control of both chambers, only Homeland Security and Defense appropriations were enacted that year, with a CR covering the remainder of federal agencies for the rest of the fiscal year enacted Feb. 15, 2007.

If Democrats take control of one or both chambers, they’re faced with a decision on appropriations. Will they play ball like Senate Republicans did in the 2014 lame duck, or do they kick the can into the new year and potentially delay the next spending season? So far, Democrats are making noises indicating they want to get back to “regular order” and work through the spending bills, regardless of electoral machinations.

“We’ve been working very closely together. We want to make it as seamless as possible. We want to put the Appropriations Committee back to being what it should be,” Senate Appropriations ranking member Patrick J. Leahy of Vermont said.

Internal races, ‘rescissions’

Another complication for fiscal 2019 beyond the midterms is that key Republican players on spending — House Speaker Paul D. Ryan of Wisconsin and Rep. Rodney Frelinghuysen of New Jersey — have both announced their retirement. Contenders positioning themselves to move up in the ranks might take opposing stances on must-pass legislation such as spending bills to try to win friends and influence with different factions who could be helpful.

Regardless, appropriations leaders in the House and Senate have set a rigorous schedule, with the House panel’s first full committee markup expected May 8. Subcommittee markups could begin as early as this week, according to Jennifer Hing, the panel’s communications director.

In the Senate, Republicans want to see committee-reported bills on the floor in June, in hopes of breaking the recent cycle of declining to put most of the spending measures on the floor to chew up valuable time and subject members to tough votes.

Senate Appropriations Chairman Richard C. Shelby of Alabama said last week he was aligned with Trump’s ultimatum of avoiding another massive omnibus bill, which limits options in terms of truncating the process.

Sen. Steve Daines, an appropriations member, said that could mean the Senate works on bills in bunches, known as “minibuses.”

“Work together on this and minimize the drama and maximize the output,” the Montana Republican said, describing Senate appropriators’ goals.

Leadership changes could be important because they could influence priorities in spending. That’s already on display with differing opinions among House Republicans running for Appropriations chairman on a potential package of “rescissions” of unspent funds from prior bills, including the fiscal 2018 omnibus.

The prospect of a rescissions request, or multiple such measures as Office of Management and Budget Director Mick Mulvaney suggested last week, is already threatening to roil bipartisan agreement on appropriations.

Democrats and many Republicans say a deal’s a deal on fiscal years 2018 and 2019 spending, and trust would be out the window if the GOP backed up Trump’s demands to cut previously-approved fiscal 2018 spending.

Senate Republicans in particular have expressed little interest in rescissions, so there’s still a chance the issue fades into the background and allows bipartisan comity. But with Trump’s bully pulpit and Twitter megaphone, that’s an uncertain prospect.

Jennifer Shutt contributed to this report.