Interior held back FOIA’d documents after political screenings

Watchdog: ‘Are there bad actors at these agencies that are willfully ignoring the law?’

Documents sought under the Freedom of Information Act were withheld by the Interior Department under a practice that allowed political appointees to review the requests, internal emails and memos show.

The policy allowed high-ranking officials to screen documents sought by news organizations, advocacy groups and whistleblowers, including files set to be released under court deadlines. In some cases, the documents’ release was merely delayed. In other cases, documents were withheld after the reviews.

CQ Roll Call first reported on the “awareness review” policy in May, but a new trove of emails show documents were plucked from release following the screenings.

Liz Hempowicz, director of public policy for the Project on Government Oversight, a nonpartisan watchdog, said after reviewing some of the emails that Congress should investigate if Interior is violating FOIA.

“Are there bad actors at these agencies that are willfully ignoring the law?” Hempowicz said. “I think we need to get to the bottom of why it’s happening and that’s going to instruct how to fix it.”

An Interior spokeswoman said the department has no policy that requires political officials to approve the release of records under FOIA.

The department, spokeswoman Molly Block said Monday, “does not have an affirmative response requirement from political officials, and has not had such a policy in this administration. … Any suggestion to the contrary is clearly driven by political motives.”

“Because there have apparently been misunderstandings about this question, including in prior administrations, the Awareness Review Process was formalized in writing for the first time by this administration,” she said in an email. “This policy is posted on the department website for all to see, and clearly states that a reviewer has no more than three working days to conclude his or her review. Thereafter the decision to release responsive records is made by a career, nonpolitical FOIA officer, in conjunction with the advice of a career, nonpolitical departmental attorney.”

The policy, which was formalized in May 2018 and updated in February, does not specifically say if documents may or may not be withheld after review.

But internal Interior emails, notes and memos Earthjustice gathered through a lawsuit and provided to CQ Roll Call show political staffers regularly delayed the release of government records. In some cases, records were prevented from release following the reviews.

The documents show Interior in a different light than a 2015 inspector general report, which Senate Republicans requested, that found political tinkering in “rare” instances. But the IG said it “remained free from political influence.”

Earthjustice and two other environmental groups, Sierra Club and Friends of the Earth, sent a letter Friday to Interior’s acting inspector general, Gail S. Ennis, demanding her office investigate the policy.

“The awareness review process implemented by staff at the department clearly goes beyond the process detailed in the Feb. 28, 2019, memo,” the letter reads, alluding to the policy update that month. “These policies and practices are unnecessary for Interior to meet the act’s requirements and in fact, have caused the agency to repeated[ly] violate the act.”

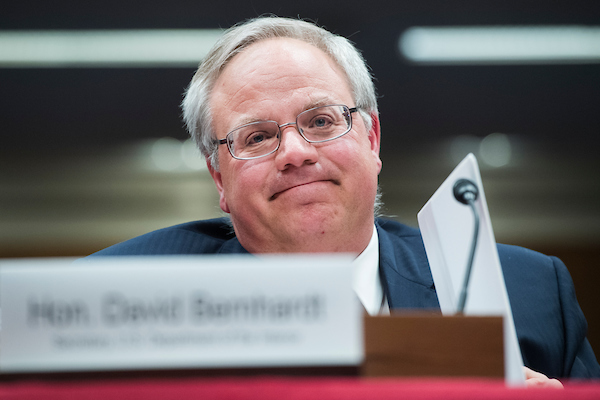

At a hearing last month, Sen. Patrick J. Leahy of Vermont, the top Democrat on the Senate Appropriations Committee, asked Interior Secretary David Bernhardt about the practice, which he defended.

“It’s a process that’s very long-standing in the department,” Bernhardt told the committee. “We definitely formalized it.”

Delays

In July 2018, Interior Press Secretary Heather Swift asked FOIA officials to delay the release of records because she was on holiday. Swift is a political appointee but is no longer press secretary.

“Sorry to be a pain but I am on vacation right now. Can we hold this until I return on Tuesday,” Swift wrote in a July 12, 2018, email.

In other instances, the policy forced FOIA officers to wait until hearing from political employees before releasing records.

After Joel Clement, a whistleblower, sued the department under FOIA to release records about being reassigned from his post, Interior Communications Director Laura Rigas interceded. Career FOIA officials in March 2018 identified 1,558 pages of “responsive” documents it planned to release — a number that was eventually pared down to just 49 after the review process.

“I have concerns about items in here [redacted],” Rigas said to Ryan McQuighan, a career records official.

Days later, McQuighan wrote back that he would work with an attorney in the solicitor’s office on a “revised package” and that other political officials, including Rigas, would “still need to clear this.”

“Deadline for this FOIA was last Friday, so we need to get affirmative response soon,” he wrote.

Later that day, McQuighan replied that Casey Hammond, an aide to then-Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke, “helped me figure this out by commenting about a non-responsive page” and now “it makes sense to me why Laura was asking this question.”

“The only file to be released for this FOIA is the 56 page attachment,” McQuighan said. According to court documents, the department released 49 to Clement.

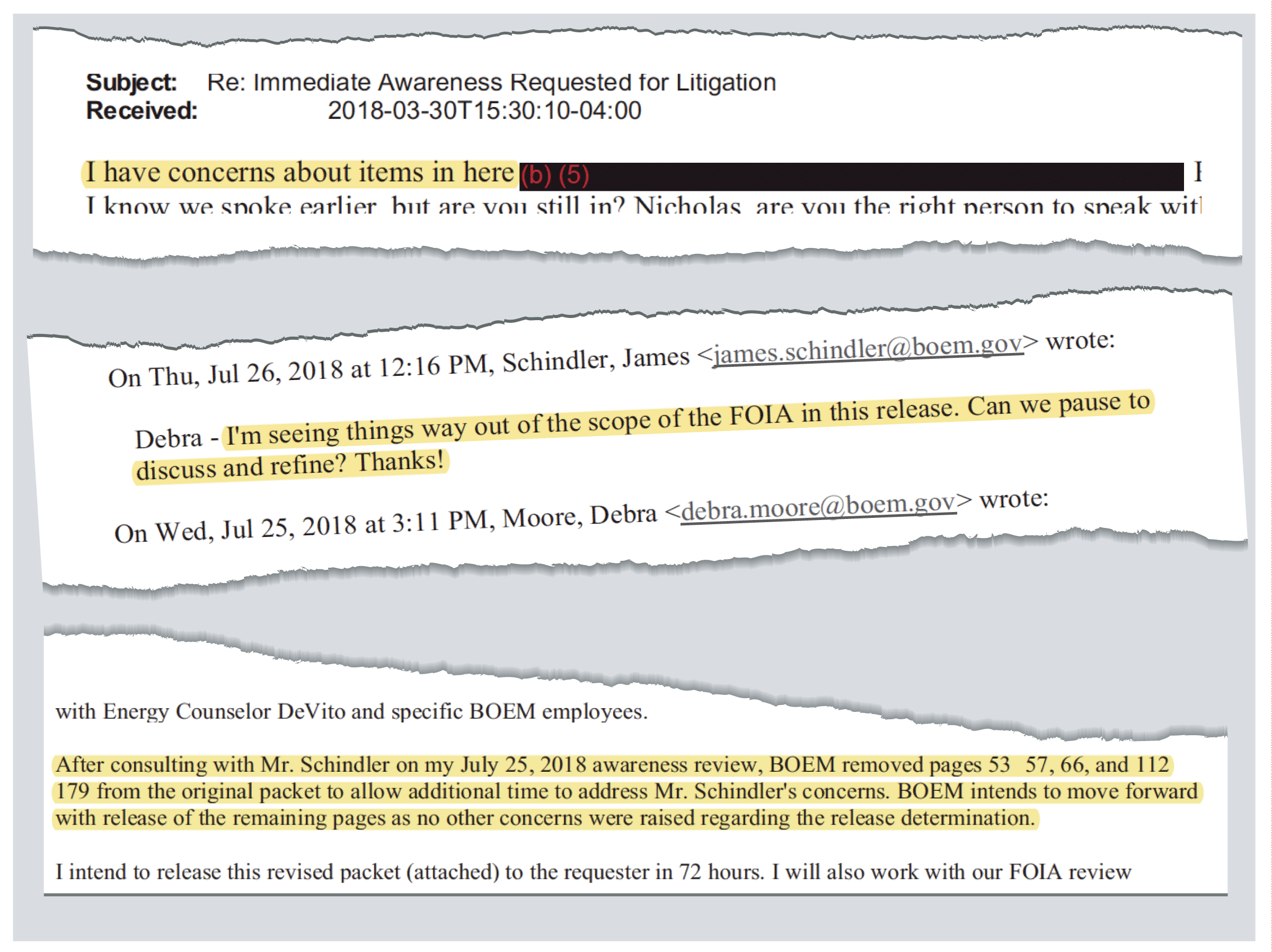

In another case, James Schindler, a political employee, voiced concerns about records that might be covered in a FOIA request to the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, a division of Interior.

“I’m seeing things way out of the scope of the FOIA in this release,” he wrote a records official at BOEM. “Can we pause to discuss and refine?”

A week later, that official, Debra Moore, said BOEM had eliminated pages from what had been set for release.

“After consulting with Mr. Schindler on my July 25, 2018 awareness review, BOEM removed pages 53 57, 66, and 112 179 from the original packet to allow additional time to address Mr. Schindler’s concerns,” Moore wrote in an email. “I intend to release this revised packet (attached) to the requester in 72 hours. I will also work with our FOIA review attorney, Mr. Gurney Small (cc’d here) on the removed pages to come to resolution on the concerns raised by Mr. Schindler.”

Moore said after removing some of the documents that Schindler had “cleared” the release.

Legally sound?

FOIA specialists said the heavy redactions in the email exchanges make it unclear if the replies from political staff are legally sound justifications to withhold or redact documents. They emphasized that FOIA officers are typically most qualified to determine what should or should not be released.

“There is something wrong with them making the determination if they’re basing their decision on political calculations and not the letter of the law,” Hempowicz said.

“Henry Kissinger was really famous for saying, ‘Don’t put it in writing if you don’t want it to be FOIA’d,’” Lauren Harper, communications director and FOIA expert at the National Security Archive, an independent research institution at George Washington University, said in an interview.

Anyone can request information under FOIA, and requesters do not need to justify or explain their rationale. While the law provides exemptions to what can be disclosed — national security, personal files, medical information, trade secrets and law enforcement records have their own exemptions — it does not list political interests as one of those exclusions.

Tom Susman, director of governmental affairs for the American Bar Association and a member of the National Archives’ FOIA committee, said the practice appeared designed to limit political embarrassment.

“These records were originally collected by professionals who do this for a living,” said Susman, who helped write amendments to the law in the 1970s. “There certainly ought to be a presumption of regularity in the collection of those documents, and so a last-minute veto requirement for a personal sign-off by an individual seems designed to undermine the Freedom of Information Act process.”