The political gospel of Karamo Brown

Can the ‘Queer Eye’ star’s message of inclusiveness succeed in polarized times?

Karamo Brown talks like a man who has spent many hours in introspection. His speech is steeped in the language of therapy, peppered with words like “trauma” and “healing” and “boundaries.” He wants people to live their truth and accept who they are so they can be better for the people around them.

It should come as no surprise that the former social worker talks this way — especially to anyone who watches Brown on Netflix’s “Queer Eye,” a runaway television hit that preaches inclusion and asks its audience and subjects to accept people who are different from themselves.

Originally airing in 2004, “Queer Eye” got a Netflix reboot in 2018. The series stars five gay men who specialize in makeovers, from fashion and home design to grooming, culture, and food and wine. Whether it’s two sisters expanding their barbecue business or a self-deprecating app developer gaining confidence, the transformations tug on your heartstrings. The show functions as an antidote to the political polarization currently roiling the country — or at least that’s the goal.

Brown, 38, plays the part of Culture Guy on “Queer Eye.” It’s his job to help people search within themselves, and he certainly has a wellspring of life experience to draw from. He talks candidly in his recent memoir (“Karamo Brown: My Story of Embracing Purpose, Healing, and Hope”) about his former addictions: Drugs. Alcohol. Food. Exercise. Pornography. He talks about the physical abuse he witnessed his father inflict upon his mother. He even talks about the physical abuse he inflicted upon his own partners. Karamo Brown believes talking about your issues openly is the way to get to the bottom of them, embracing past mistakes instead of running from them.

And he practices what he preaches. In his memoir, published in March, he details how he horrified his mother by snorting cocaine in front of her en route to a New Year’s Eve party.

But can this message of openness, vulnerability and unity infiltrate modern politics, a system rife with polarization?

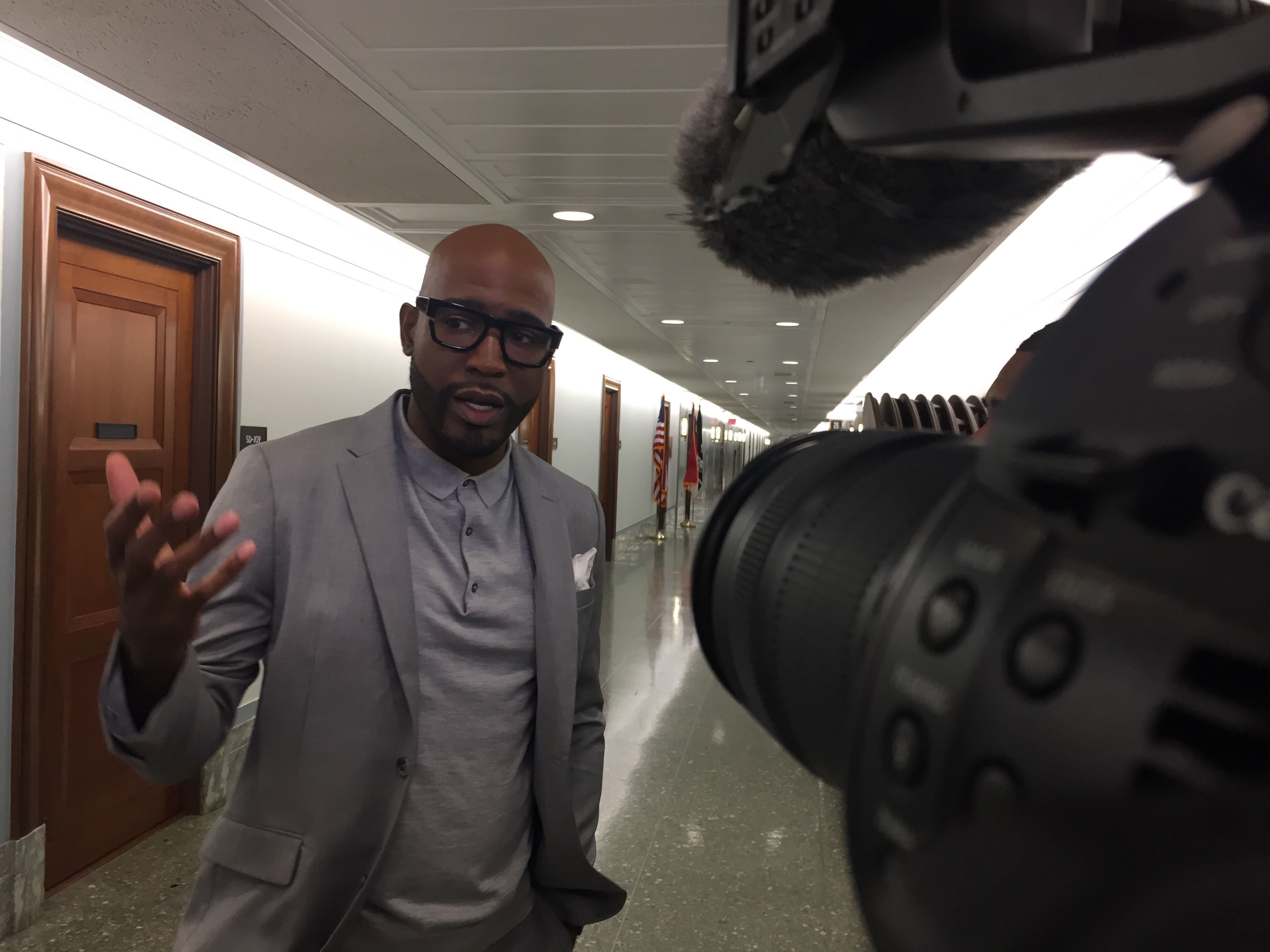

The reality TV star and activist is determined to find out. He hopes to use his experiences to change laws. He’s made several trips to D.C., working with former President Barack Obama’s My Brother’s Keeper Alliance. Last year he met with the staff of second lady Karen Pence to discuss arts funding — a visit that fueled speculation that Brown was a big supporter of President Donald Trump. (Not true, Brown tells me. “I didn’t” vote for the current president, he says.)

That brings us to Wednesday, when Brown brought his message of inclusivity to Capitol Hill to push for legislation that would prohibit LGBTQ parents from being discriminated against in the adoption and foster care process.

During a panel discussion Brown spoke about his personal experience as a single gay man and the difficulty he faced trying to adopt. These “challenges and hurdles were trying to stop me from giving my child the love he deserves,” he says. He likened restrictions against LGBTQ adoptive parents to someone starving who turns down food because they “don’t like who prepared the meal.”

Less than half of the 120,000 children waiting for adoption in the U.S. foster care system will find an adopted family, according to the Family Equality Council. And about 20,000 children “age out” of foster care each year.

Life can be particularly harrowing for children who are never adopted. One panelist, Kristopher Sharp, told a gut-wrenching story about having more than 20 foster placements without an adoption. At age 13, he was sexually molested. Once he left the program he became homeless, turning to prostitution before eventually contracting HIV.

Brown and the council argue that with so many children in need of a home, it’s “ridiculous” that states would have restrictions against gay parents looking to adopt.

Rep. John Lewis and Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand are soon expected to introduce the Every Child Deserves a Family Act, which would withhold federal funding from child welfare agencies that exclude potential adoptive and foster parents because of their sexual orientation, gender identity or marital status.

Though he supports the measure by Gillibrand, who is currently seeking the Democratic nomination for president, Brown isn’t ready to make any endorsements.

When asked who he’s backing in 2020, Brown says it’s still early but he’s looking for someone who “has the best shot of bringing together both parties,” before adding “we’re tired of being divided.”

He doesn’t rule out someday running for office himself, calling it a “strong possibility.” But first he wants to work on the issues he cares deeply about.

“Because we have a reality star in the highest office, I get embarrassed of saying, ‘Yes, I want to go into politics,’” he says. “But what I’m trying to show people is that if and when that day comes, I’m doing the work beforehand. I’m advocating for what’s right.”

Should he someday run, Brown says he’s not concerned about showing vulnerability in the rough-and-tumble world of politics, where political enemies dig up past dirt to bring down opponents.

“You need someone who is going to be honest and open and vulnerable and say, ‘This is the truth of the matter,’” says Brown. “That’s why I am always willing to share my personal stories so that people can understand that I’ve been through it, that I understand their challenges, and let’s move on from there.”