Their Districts Are at Risk. But They Still Vote ‘No’ on Climate Action

High waters and toxic blooms haven’t scared these lawmakers

He lives just half a mile away from the beach in Sarasota, Florida, but Len Seligman, a local musician, has barely enjoyed the sun and sand by the waterside recently, discouraged by the stench of dead fish and other marine animals washed ashore, poisoned by toxic algal blooms.

“In the last few months, there have only been a few days that it’s been tolerable,” the 63-year-old retired computer researcher said. “You just can’t breathe when the red tide is bad.”

This year’s unusually stubborn algal bloom, referred to as a red tide, highlights the risks of a warming climate to fragile ecosystems in Florida and has ignited anger among voters leading up to the midterm elections.

The United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warns in a report released Oct. 7 that unless urgent and drastic action is taken, global warming could rise by 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) between 2030 and 2052, a level that climate scientists fear could have catastrophic repercussions for the environment, humans and wildlife.

Still, climate change remains a marginalized issue among politicians running in the 2018 midterms, especially Republicans.

Trump on Climate Change: ‘Something’s Happening,’ But It Could Reverse

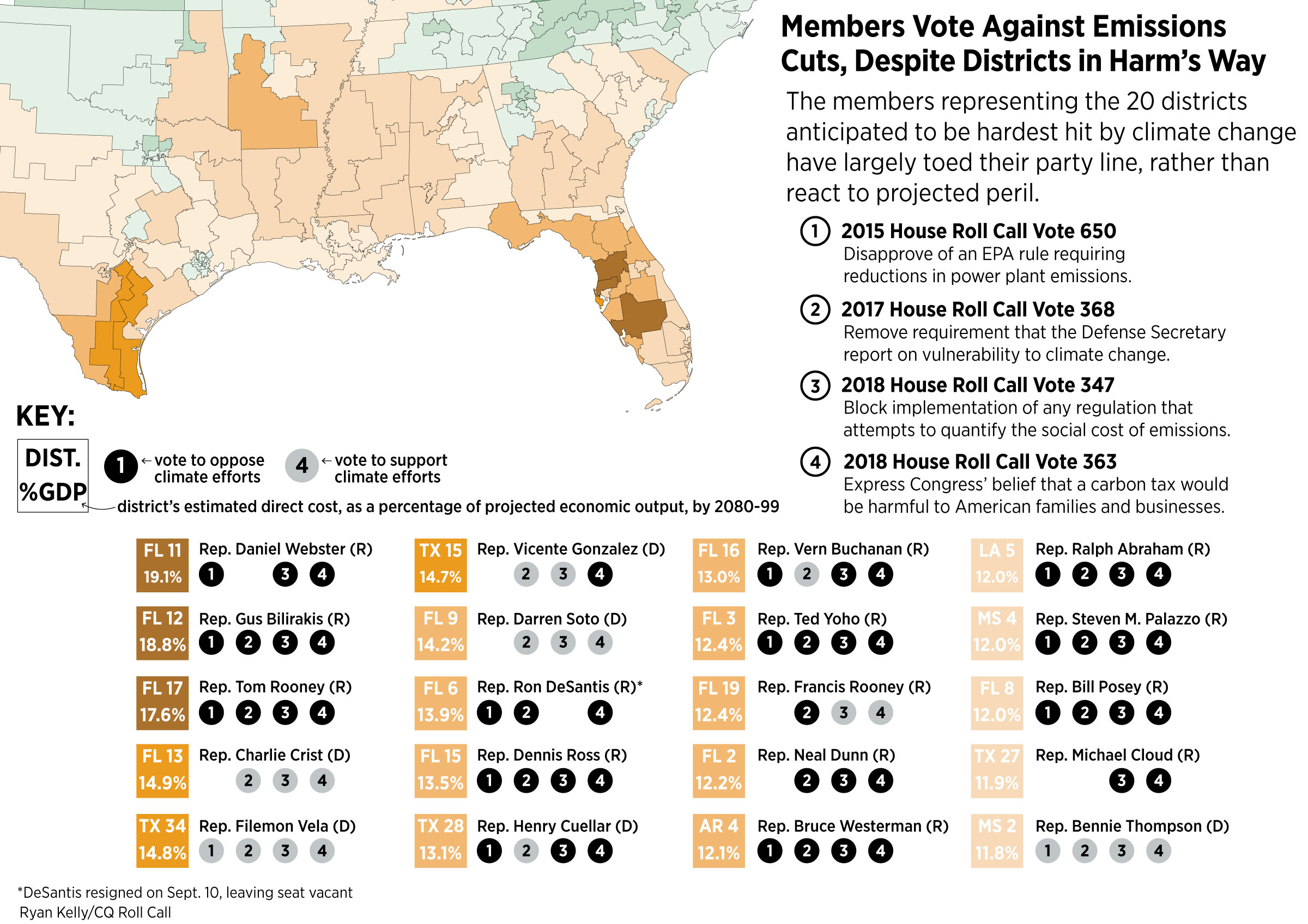

Moreover, our analysis shows that a majority of the 20 congressional districts facing the highest risk from rising sea levels, more frequent and severe storms and other climate effects by the end of the century are represented by lawmakers — mostly Republicans — who tend to vote against measures to slow global warming, such as efforts to reduce carbon emissions.

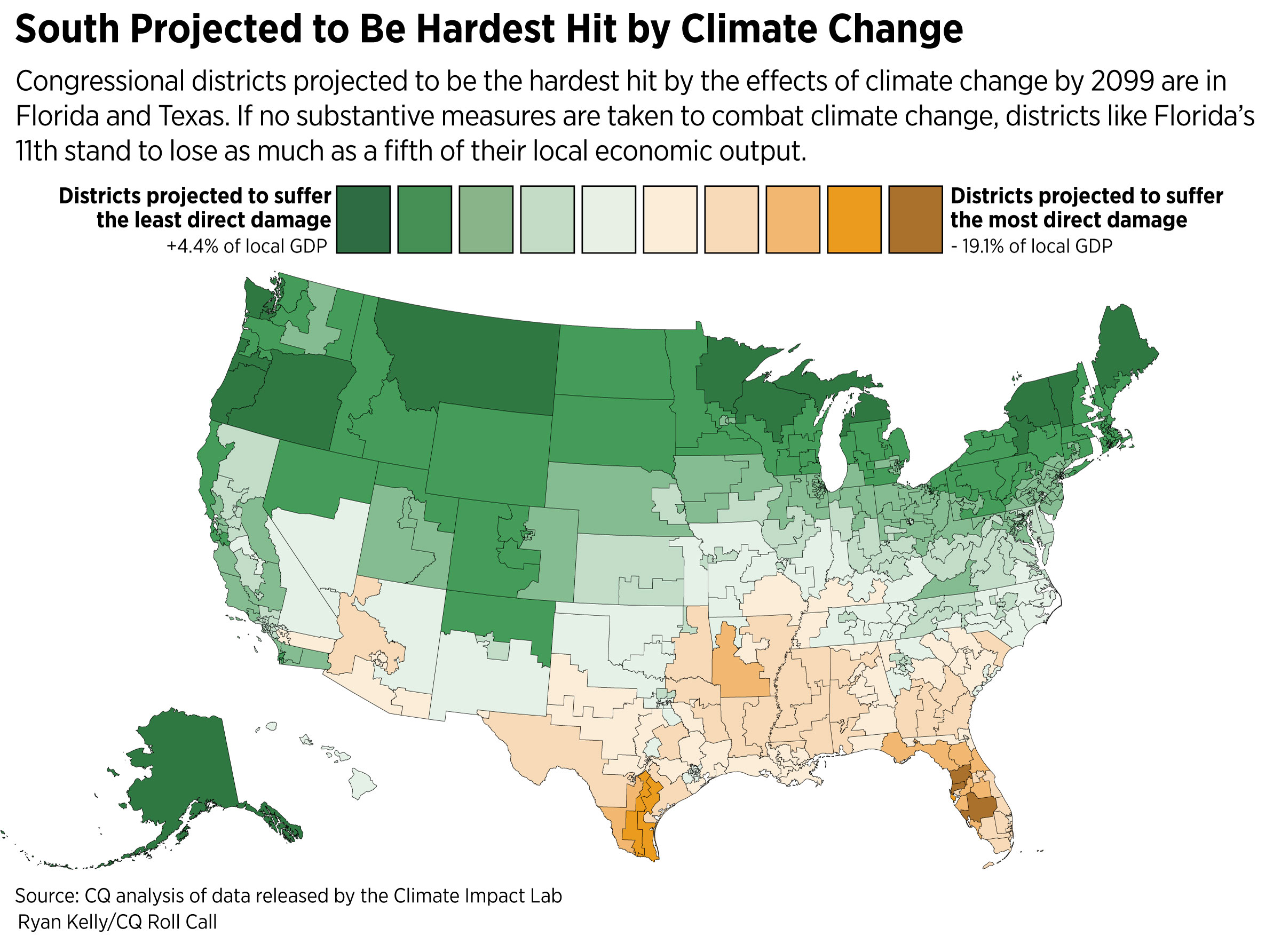

To come up with the 20 districts, we combined and analyzed data from two reports: one by Climate Impact Lab, published in Science magazine, projecting the economic damage that could result from climate change between 2080 and 2099 in the U.S., and another by researchers at Yale and George Mason universities that gauged opinions on climate change in different communities.

Seligman resides in Florida’s 16th District on the Gulf coast. For the November midterms, the district is rated Likely Republican by Inside Elections with Nathan L. Gonzales. It’s also one of the 20 high-risk districts.

The issue will be on Seligman’s mind when he votes next month in the race between incumbent Republican Rep. Vern Buchanan and Democratic challenger David Shapiro.

“Yes, I’m paying attention. David Shapiro is far better on environmental issues, including climate change, and he will get my vote,” said Seligman, who considers himself a liberal Democrat but also has voted for Republicans. “Buchanan is terrible on many issues, including the environment and climate change.”

Buchanan’s campaign website makes no mention of the environment or climate change and he supports more drilling for oil and gas. Still, he was among four congressional Republicans who in a letter last year urged President Donald Trump to keep the U.S. in the Paris Agreement.

“Climate change is a serious issue, especially for a state like Florida that has two coastlines vulnerable to rising waters,” Buchanan said. “Protecting the environment and growing the economy are not mutually exclusive. We should be doing everything we can to accomplish both.”

At the same time, he has voted against three of four key climate change mitigation measures that we used to gauge the voting records of lawmakers representing those 20 high-risk districts.

Twelve of the districts are in Florida, where a fragile ecosystem is already facing a slew of problems, including coastal erosion, damage to the Everglades and flooding.

Scary stakes

NASA scientists warn that climate-related events such as droughts, wildfires, more intense and frequent hurricanes, rising sea levels, extreme summers and winters, and melting glacial ice are already affecting local economies, agriculture, infrastructure and public health.

Last year was the second-warmest since record-keeping began in 1880, according to the space agency’s analysis, and coastal communities, including in Florida, Texas and North Carolina, have borne record-breaking hurricanes and storms.

“It would be risky not to be focused on it in Florida, and irresponsible,” said Democratic Rep. Charlie Crist, who is seeking re-election in Florida’s 13th District, which includes St. Petersburg and is among those 20 most threatened. “The district that I represent is a peninsula, and a peninsula in Florida … it’s a huge issue here.”

The other districts on the list are in Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi and Texas. Republicans represent 13 of them, and six are represented by Democrats. One seat is vacant since its representative, Florida Republican Ron DeSantis, resigned to run for governor.

Republicans have generally been more likely to vote against measures to combat climate change than their Democratic cohorts, partly because many conservatives claim to be skeptical of climate science or the extent of human contribution to global warming. And when climate change is acknowledged, conservatives have tended to shy away from solutions they view as harmful to industry or that would hamper energy development.

“Instead of discussing costly nonsolutions, candidates should use this opportunity to offer better plans for natural disaster response, resilience and preparedness that will actually make a difference in protecting households and businesses in those areas,” said Nicolas Loris, an economist focusing on energy, environmental and regulatory issues at the conservative Heritage Foundation.

Even where Republicans have campaign messages about climate change and the environment, our analysis shows that for most, their statements are not consistent with their voting record on key climate measures.

“It’s still a risky issue,” Loris said. “In some areas in the past where Republicans have supported issues like a carbon tax, they have been voted out quickly.”

Indeed, a survey by the Pew Research Center released in September found that Democratic voters — 82 percent — are far more likely than Republicans — 38 percent — to say the environment is very important in winning their vote.

“There is certainly an opportunity for Republicans to talk about productive solutions for how to address and mitigate those issues,” Loris said. “Politicians need to be thinking of how to address those concerns in a way that is understandable to their voters.”

Our assessment of the votes of the representatives of the 20 high-risk districts shows that most of them have voted to pass measures that would almost certainly increase that risk. Most of those lawmakers are running for re-election in November.

Carbon tax opposed

In July, 15 representatives of the districts voted to pass a resolution introduced by Majority Whip Steve Scalise, a Louisiana Republican, rejecting a carbon tax as a way to control greenhouse gas emissions, the biggest culprit in global warming. All but two, Texas Democrats Vicente Gonzalez and Henry Cuellar, were Republicans.

Florida Republican Rep. Francis Rooney voted against the resolution, as did the four other Democrats in the group.

Ignoring social costs

In July, 13 representatives from the 20 districts voted for an amendment introduced by Oklahoma GOP Rep. Markwayne Mullin to the fiscal 2019 Interior-Environment spending bill that would prohibit the federal government from considering the social cost of carbon in rulemakings.

The metric used by the government was devised by the Obama administration to calculate the long-term monetary damage from greenhouse gas emissions and to measure the climate impact of rules to control such pollution. The calculation formed the basis for many Obama administration Clean Air Act rules, most of which have been rejected by conservatives as costly and burdensome to industry.

Cuellar was again the only Democrat to support the measure, and Rooney was the only Republican to vote against it.

“Rising sea levels, increased intensity of hurricanes and more coastal flooding, as recently highlighted by Hurricane Irma, are existential threats to our Southwest Florida community,” Rooney said.

“I am committed to raising awareness of these risks and of the need for proactive planning to mitigate future effects of environmental disasters,” he said. “This is why I recently joined the Climate Solutions Caucus and introduced a resolution describing the negative impacts of sea level rise on Florida.”

Rooney’s resolution, which has not received a vote, recognizes that “sea level rise and flooding are of urgent concern impacting Florida that require proactive measures for community planning and the state’s tourism-based economy to adapt.”

The bipartisan Climate Solutions Caucus was co-founded by Florida Republican Rep. Carlos Curbelo, whose 26th District on the southern tip of Florida, though not in the top 20 for risk, faces high risk for sea level rise, flood and infrastructure damage. It’s rated Tilts Republican by Inside Elections.

Blocking defense planning

In July 2017, several Republicans joined Democrats in defeating an amendment by Rep. Scott Perry, a Pennsylvania Republican, to the 2018 Defense spending bill that would have stripped a requirement in the measure that the agency plan for global warming and rising sea level threats.

But 12 of the representatives from the high-risk districts voted for the amendment. All 12 were Republicans. Buchanan voted against the amendment, while Rep. Michael Cloud, another Republican from Texas’ 27th District, had not yet taken office. All seven Democrats voted against the Perry amendment.

Clean power plan dissed

In December 2015, the House adopted a resolution disapproving the Clean Power Plan, the most ambitious attempt by the Obama administration to cut greenhouse gases from power plants nationwide.

Twelve of the 20 representatives, including one Democrat, Cuellar, voted for the resolution. Six others had not yet been elected to Congress. Two Democrats voted against it.

“The fact is that the traditional energy sector employs thousands of people and contributes tens of millions of dollars to local schools in the form of royalties and property taxes,” Cuellar said in an emailed statement, adding that his county owes its wealth to the discovery of shale deposits there. “So, when we talk about energy and the environment, we need to consider how we can support both endeavors.”

Science snubbed

None of the Republicans from the most vulnerable districts signed on to a GOP resolution stipulating that it is a “conservative principle to protect, conserve, and be good stewards of our environment, responsibly plan for all market factors, and base our policy decisions in science and quantifiable facts on the ground.” Introduced in March 2017 by GOP Reps. Elise Stefanik of New York, Ryan A. Costello of Pennsylvania and Curbelo, it has attracted just 23 Republicans so far.

Overall, more than half of congressional districts that have the most to lose from climate change are represented by lawmakers who have voted to reject measures to slow global warming.

Alyssa Roberts, a spokeswoman for the League of Conservation Voters, says more and more Republicans are using rhetoric that does not match their voting records as they face tough races in areas where the environment is a priority for voters.

“It’s an attempt to trick voters into thinking that one supports climate action,” Roberts said, citing Republicans like Rick Scott, the Florida governor running for the Senate whose environmental record has come under scrutiny in the aftermath of the red tide, and Rep. Mimi Walters of California, who faces a tough re-election bid in a state and district that has experienced intense wildfires.

Walters, who has consistently voted against climate change mitigation proposals, faces a re-election challenge from University of California, Irvine, professor Katie Porter in a race that is rated a Toss-up by Inside Elections.

In August, Walters joined five other members of the House Climate Solutions Caucus of which she is a member, in signing a letter to California Gov. Jerry Brown tying the wildfires that have ravaged the state to climate change.

“We know that the larger wildfires in California and Western states are being fueled by climate change,” said the letter, which invited Brown to meet with the caucus.

In July, Walters signed on to a caucus letter to Defense Secretary James Mattis rebuking the Pentagon for reportedly removing references to climate change and its risks to military bases from a new version of a report previously written in the Obama administration.

Meanwhile, climate change is not listed as one of the priority issues on her campaign website. And her votes in Congress have been against climate action, causing her mention of climate change to be viewed with skepticism.

While Walters, who did not respond to a request for comment, voted against the Perry amendment in the fiscal 2018 Defense spending bill, she voted for the bill prohibiting the use of the social cost of carbon, the resolution rejecting the Clean Power Plan and Scalise’s carbon tax resolution.

Vulnerable Republicans acknowledging climate change but not voting to respond to it shows they’re “out of step with their voters,” Roberts said.

Environmental groups are taking no chances, spending big dollars to highlight environmental issues and back supportive candidates, especially in at-risk districts and in campaigns with vulnerable Republicans.

The goal is to usher in a pro-environment majority in Congress, they say, to fight the rollbacks of regulations meant to protect safe water, clean air and public health that have been targeted by congressional Republicans and the Trump administration.

The League of Conservation Voters expects to spend a record $60 million on the midterms this year. The Sierra Club plans to spend more than $6 million, and the Environmental Defense Action Fund expects to spend $6 million on federal races and $1 million on state and local races.

By Oct. 3, a joint initiative dubbed GiveGreen by several environmental groups had raised more than $14 million for federal and state candidates through grass-roots giving, surpassing the $8.4 million it raised during the 2016 election cycle.

“The choice has never been plainer than it is this year,” Tom Steyer, president of NextGen America, said in a statement announcing the record fundraising. “We need to elect candidates who will protect our environment, or else we will watch as Republicans continue to push policies that inflict irreversible damage on our planet, solely for the sake of corporate profits.”