Kennedy and Nixon Before Camelot, Watergate

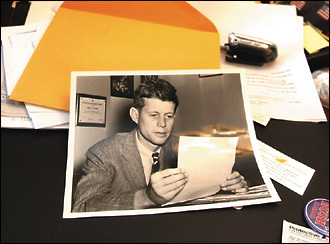

Not long after Rep. Jo Bonner (R-Ala.) moved into Cannon House Office Building 315 — part of the former digs of then-Rep. John F. Kennedy (D-Mass.) — his mind began to play tricks on him. [IMGCAP(1)]

In the wee hours of a late-night budget markup, the then-freshman’s thoughts drifted back to Kennedy’s early days on Capitol Hill in the late 1940s, when JFK and another freshman Member, California Republican Richard Nixon, were still colleagues, not yet rivals. That Bonner’s staff had recently mentioned a strong “smell of smoke every morning when they came in” only fueled his highly caffeinated imagination.

“I had read somewhere that young Jack Kennedy liked to come over when it was late at night and he was here, and light up a cigar. And so you know, your mind starts to wonder.

“I don’t believe in ghosts and I certainly was not believing there were any spirits in the office, but I was telling someone over on the floor about the fact that I have Congressman Kennedy’s office and that there seemed to be a pronounced odor of tobacco and someone else heard about that … and finally I had one of my colleagues [Rep. Thaddeus McCotter, R-Mich.] who said, ‘Bonner, don’t get any wild rumors going. I smoke like a chimney and I’m in the office above you.’”

Bonner chuckles at the memory.

He takes seriously the legacy of being part of a select group of Members who now inhabit one of the Congressional offices occupied by Kennedy or Nixon during their respective Capitol Hill careers.

“This place is filled with history,” Bonner says, pointing out that the first woman elected to the House, Jeannette Rankin (R-Mont.), and a former vice president, then-Rep. John Nance Garner (D-Texas), at one time also had his office.

“That’s the thing that is sometimes lost on us when we are debating Social Security and ethics wars and things like that. A lot of people came and made this place what it is today long before the current Members, and we should pause at times to reflect on their service.” [IMGCAP(2)]

When it comes to Kennedy and Nixon, perhaps no two former Members’ lives in the past 50-odd years have stoked the public’s imagination as much or had a greater national impact. Both Kennedy and Nixon entered the House at the start of the 80th Congress and went on to serve in the Senate. (As vice president from 1953 to 1961, Nixon later served as President of the Senate.)

Both men were young, ambitious and staunchly anti-communist. And both would go on to hold their nation’s highest office during the throes of the Cold War.

“They weren’t that far apart on their views of things,” says Senate Associate Historian Don Ritchie, noting that prior to their face-off in the 1960 presidential campaign, the two were actually quite friendly and shared similar views on many issues.

A look at the Kennedy-Nixon offices uncovers a few notable coincidences. Senate Majority Whip Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.), for instance, says that he and the 37th president’s “paths keep crossing.”

McConnell cast his first presidential vote for Nixon in 1960 at a time when his family had the only automobile in their heavily Catholic neighborhood with a pro-Nixon bumper sticker.

In 1994, the same year Nixon died, McConnell moved into a Russell Senate Office Building suite that includes rooms once occupied by Nixon — today, they’re Rooms 355, 357 and 359. “The first desk I had in the Senate,” he said, “I opened the drawer and Nixon’s name was in it.”

Then, when McConnell was elevated to Senate Majority Whip in 2003, his new leadership office contained a plaque indicating that Kennedy had occupied it after he received the Democratic nomination for president, from July 13, 1960, to January 20, 1961. It is officially known as the John Fitzgerald Kennedy Room.

Bonner, for his part, says he’s under no illusions that his office selection means Kennedy’s career path will be his destiny. Nor, he acknowledges, does he sport the same look. “He had a lot more hair than I did,” laughs Bonner, who is, shall we say, follically challenged. “He was a really good-looking young man.”

Just next door to Bonner’s digs, in Cannon 317 — also part of Kennedy’s old House suite — a tan, young political scion recently took up residence: Freshman Rep. Connie Mack IV (R-Fla.).

In fact, Mack, whose father, great-grandfather, step-great-grandfather and great-great grandfather all served in Congress, wasn’t aware of the famous former inhabitant until it was brought to his attention for this story.

“It takes on a whole new meaning for our office, that we share space and history with someone that had such a huge impact on this country,” Mack says.

On a recent office visit, Mack’s blinds were drawn — the better to keep out a rather abysmal view of “the inner workings of the Cannon building,” including such riveting features as the air conditioning system. Asked what he believes Kennedy might have thought as he gazed out the window, Mack shoots back: “I need a new office.”

Which may have been what Rep. Chris Chocola (R-Ind.) was pondering back in November 2002 when his chief of staff, Brooks Kochvar, first informed him he’d drawn 46 out of 53 in the freshman office lottery. That landed them on the fifth floor of Cannon and, as they ultimately discovered, in part of Nixon’s old House office. Kochvar notes that despite the office’s remote location, it offered views of the Capitol Dome and “the top 10 feet” of the Washington Monument.

Shortly after moving into Cannon 510, Chocola recalls former Rep. Dan Miller (R-Fla.), a prior occupant, telling him it had been Nixon’s House office. So Chocola jokingly mentioned the fact in passing a few times, which led to an enterprising South Bend Tribune reporter confronting him about his assertions.

The reporter, who had since learned that Nixon’s old House office number was Cannon 528, called the office and said, “You told me about this [being] Richard Nixon’s old office. Prove it,” Chocola recalls, adding, “I said, ‘I don’t want to prove it.’” But then the reporter said he “might have to write something” questioning Chocola’s veracity, and the then-freshman Representative decided to rise to the occasion.

Turns out they were both right. Cannon 528 became 510 when the offices were renumbered after the opening of the Rayburn House Office Building in 1965 (much as Kennedy’s House office, Cannon 322, was split between Cannon 315 and 317). Over the years, everyone from then-Reps. Tom Daschle (D-S.D.) to Norm Mineta (D-Calif.) have held the office.

It was here, in what was known as “the attic,” that Nixon was found soon after his swearing-in by a Republican National Committee photographer “working on the phone at a small desk amid bare walls, a box of envelopes … [and] a pencil sharpener still in its box atop steno pads,” according to an account in Roger Morris’ book, “Richard Milhous Nixon: The Rise of an American Politician.”

A few years later, Kennedy would stop by the office to drop off a $1,000 contribution to Nixon’s Senate campaign from his father, Joseph P. Kennedy.

Chocola, who was in elementary school when Nixon was president, says he has only one distinct childhood memory of the California Republican, aside from the ignominious way in which he left the White House.

“I was at my grandparents’ house … watching TV and they talked about President Nixon today proposed price and wage controls,” Chocola says. “It’s something I’ve always remembered and being under 10, I thought, ‘I don’t like the sound of that. It just doesn’t sound right.’”

In recent years, the Senate has put up brass plaques that indicate offices held by its members who went on to become vice president or president — a move that has attracted additional attention to those who hold such offices.

Bonner said he’s been trying to get the House Administration Committee to do the same thing for such offices in the House, so far without luck.

Occasionally, occupying a famous office can attract odd behavior. In Russell 355, McConnell recalls that “a guy walked in here and said he was looking for Nixon because he thought he was on Nixon’s enemies list and he wanted to get off the list.”

As a result of the frequency with which tourists have tried to enter what McConnell uses as a staff room, a “Do Not Enter” sign was put up a few years ago.

Though none of these Members reported setting up shrines to the famous former occupants, some Members have added, or are in the process of adding, a few touches to memorialize the fact that Nixon or Kennedy once worked there. And in several cases, the admiration runs counter to party lines.

One of these is Sen. Judd Gregg (R-N.H.), who now occupies Kennedy’s former Senate digs in what is today Russell 394, 396 and 398, joining then-Sen. Al Gore (D-Tenn.) among those who have filled that space.

While flipping through Vanity Fair magazine last year, Gregg’s wife, Kathleen, spotted a photo of Jackie Kennedy sitting at her husband’s desk in what is now Gregg’s personal office. “My goodness that’s your office,” he remembers her telling him.

So she contacted the magazine, which put her in touch with the John F. Kennedy Library in Boston. In turn, the library sent her photos of Kennedy working in the old office, which Gregg has hung in a staff room just off his personal office.

Subsequently, Kathleen Gregg also stumbled upon “either the bookends” that were on Kennedy’s desk in one of the photos or “an exact copy” in an antiques store, which Gregg now displays on his own desk. (Nixon, who was then vice president, attended social functions in Kennedy’s Senate office, says Ritchie. Nixon also visited Kennedy there when he was recovering from back surgery.)

As if that weren’t enough history, Gregg says the most interesting item in his office is a deed for a tract of land in New Hampshire signed four times by another former Massachusetts Senator, Daniel Webster. “Ironically, the guy [Webster] sold it to was named Gregg,” he notes, adding that he also sits in Webster’s former Senate desk.

Meanwhile, Bonner, after researching the former occupants and discovering the Kennedy connection, ordered a photograph of JFK from the Library of Congress and set out on a quest for “Kennedy for Congress” memorabilia.

So far, however, he’s acquired a button and a bumper sticker from Kennedy’s presidential campaign, which he’s having framed for the office, along with the photo in a mini-montage. (Kennedy Congressional memorabilia is scarce and mostly out of Bonner’s price range.)

Nixon, who would go on to resign the presidency over the Watergate scandal, received somewhat less recognition in his former offices.

McConnell had a lone framed headshot of the 37th president in a staff room, while the Chocola office lobby sports an original editorial cartoon, published in an Indiana newspaper, depicting him sitting in his office with Nixon’s ghost hovering over his shoulder.

“If I had Ronald Reagan’s office, we would have a shrine,” Chocola says. (Reagan, of course, only had an office out in Sacramento.)

So how do Members balance the intangible benefits of history with the more immediate demands of more, not to mention more attractive, space? Despite the historical legacy, some Members said they would vacate, were a better piece of Hill real estate to become available.

“I would take his brother’s office,” says Gregg of the nearby suite occupied by Sen. Edward Kennedy (D-Mass.), which has a fine view of the Capitol Dome. “I’m sure Ted will want to maybe exchange with me sometime.”