Inside the MTBE Fracas

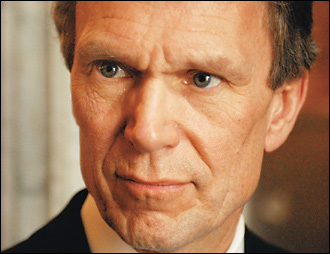

Back in 1990, Sen. Tom Daschle, a young Democrat from South Dakota and protégé of then-Senate Majority Leader George Mitchell (D-Maine), led the fight to require oil companies to produce cleaner burning fuels.

Fourteen years later, those companies contend the current Senate Minority Leader’s original plan to require oxygen content in gasoline contributed to the rash of defective product lawsuits against an oil company-produced gasoline additive, methyl tertiary butyl ether (MTBE), which adds oxygen molecules to fuel.

Congress “forced us to produce a product that otherwise never would have been produced in such quantities,” said Bob Slaughter, president of the National Petrochemical and Refiners Association. “They told the industry to do this, and now the industry is being sued for millions of dollars for something they told us to do.”

That’s the reason oil companies, refineries and petrochemical makers now insist on an energy bill that gives them liability protection from the scores of lawsuits that claim the companies knew all along that MTBE is a groundwater pollutant.

Though MTBE has not been classified by the Environmental Protection Agency as a carcinogen, it is suspected of being a cancer-causing agent, and its foul taste and smell make water unpotable.

That has caused more than 60 communities and states in the West and Northeast to file lawsuits alleging MTBE groundwater contamination, according to the Environmental Working Group.

To protect those lawsuits from being thrown out, a bipartisan coalition of Senators led the successful filibuster of the $31 billion comprehensive energy bill last fall, and the issue continues to be the sticking point between House and Senate negotiators on the bill.

House Majority Leader Tom DeLay (R-Texas) has repeatedly refused to even consider the Senate’s slimmed-down, $14 billion energy bill, because it doesn’t contain the MTBE liability waiver.

At least 14 MTBE makers have facilities in the home state of DeLay, who declined to be interviewed for this article.

The MTBE issue is much more complicated than oil companies complaining about what they say is a Congressional mandate for oxygenated fuels and environmentalists charging that DeLay and others in Congress are attempting to shield polluters from lawsuits.

It began rather simply, as a way to help parochial interests in Daschle’s home state — corn growers who turn their crops into ethanol.

And he wasn’t alone. Then-Senate Minority Leader Bob Dole (R-Kan.) and Sen. Tom Harkin (D-Iowa) are credited with co-authoring Daschle’s successful amendment to the 1990 Clean Air Act. And 66 Senators voted with the trio on a procedural vote to save the amendment from failing.

Harkin recently recalled the fervor with which the oil industry opposed using ethanol as an additive to gasoline.

“They were taking ads out in magazines saying that ethanol would gum up your spark plugs. It was pure B.S.,” he said.

Slaughter, who was an Amoco lobbyist at the time, said oil companies did vigorously fight the Daschle-Dole-Harkin amendment. He said oil companies were already in the process of looking for cleaner burning fuels as a way to deal with the carbon monoxide and ozone problems that many cities were experiencing in the late 1980s.

“We needed performance standards, not a recipe for gas,” Slaughter said.

Along with automakers, oil companies began testing a variety of fuels in 1990. While many companies went ahead and offered reformulated (or oxygenated) gasoline prior to the Congressional mandate as a way to improve cars’ performance, others preferred to fight what they called “government gas.”

During the 1990 debate, Daschle and others were wary of being accused of favoring one fuel over another, so they left the choice of oxygenates up to the EPA, which certified several, including MTBE.

Oil companies were already using MTBE in smaller quantities to replace the octane that lead had previously supplied. (Gasoline makers were forced to phase out leaded gasoline in the 1970s and 1980s because of pollution concerns.)

But Daschle said the information on MTBE was sketchy in 1990.

“We had reports already back then that there were serious problems with MTBE, but we were prepared to be open [to other alternative fuels],” Daschle said of the negotiations over the bill. “I was skeptical then. Unfortunately, my skepticism was borne out.”

Slaughter points out that Daschle’s own floor statements at the time acknowledged that MTBE would be much more widely used than the Senator’s preference, ethanol, if the oxygenate mandate was made law.

“Anyone familiar with the debate knows that a(n) … oxygen standard can be met by a variety of fuels,” Daschle said in a May 16, 1990, floor statement. “EPA predicts that the amendment will be met almost exclusively by MTBE, a methanol derivative.”

As Slaughter contends now, “Congress went into this with its eyes open … knowing that MTBE would be used as the primary source.”

Ed Murphy, director of marketing and refining at the American Petroleum Institute, agreed with Slaughter’s assessment.

“We’d been using it for years at much lower concentrations. There was no reason to expect that there were going to be widespread problems,” said Murphy. “There had been studies done which showed the water solubility of MTBE, and we provided those to the EPA.”

But Harkin said he was misinformed about a crucial deal that was made toward the end of negotiations on the 1990 Clean Air Act.

Harkin noted the Senate-passed version of the 1990 Clean Air Act included a 2.7 percent oxygenate mandate. During conference negotiations, however, the industry asked that the mandate be lowered to 2 percent, which was done when ethanol makers agreed to the deal.

“MTBE makers knew they could not meet the [2.7 percent] oxygenation standard with MTBE,” said Harkin. “They came in to lower that standard so they could use MTBE.”

Harkin said he did not find out about the oil industry’s motives for the change until after the conference report passed. And environmentalists charge that oil companies did not provide the EPA with all of their anecdotal evidence on MTBE’s proclivity for water pollution.

“They misrepresented to the EPA the extent of contamination in the ’70s and ’80s,” said Ken Cook, president of the Environmental Working Group.

Cook pointed to memos obtained through several lawsuits against the oil companies and MTBE makers that show what Cook said is a concerted effort to fudge the facts on MTBE.

In response to an EPA request for more information on MTBE’s effect on groundwater, a Feb. 12, 1987, memo to the agency from ARCO Chemical Co. states: “We feel there are no unique handling problems when gasoline containing MTBE is compared to hydrocarbon-only gasoline.”

However, both Exxon and Shell oil companies already had experience in trying to clean up MTBE spills in Maine and Maryland in the early 1980s. An Exxon engineer stated in a 1984 memo that “the number of well contamination incidents is expected to increase three times following the widespread introduction of MTBE into Exxon gasoline.”

API’s Murphy agreed that the industry initially favored MTBE over ethanol, which was more costly and in some cases had been found to increase greenhouse gas emissions in the summer months.

“Essentially, it was a more cost-effective additive,” he said.

Of course, by using the lower-cost MTBE over ethanol, oil companies thwarted the goal of Daschle and Harkin to encourage the production of corn-based ethanol — an effort they have renewed in this year’s energy bill.

And since a number of states — such as California and New Hampshire — have banned MTBE, ethanol is finally taking off.

“We got about 15 percent of the market in the early years,” said one ethanol industry spokesman. “We’ve got up to 50 percent today. Over 50 percent of reformulated gas is blended with ethanol.”

But with Congressional opponents of ethanol use like Sens. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) and Judd Gregg (R-N.H.) pressing the EPA to exempt their states from the 2 percent oxygenate requirement, even the cleaner-burning ethanol could be in trouble.

“You have to use it whether you need it or not,” complained Feinstein. “We can meet our clean air standards without an oxygenate.”

It’s an argument eerily similar to the one oil companies were making 14 years ago.