The Gentrification Debate

Capitol Hill Residents Question the Effects of Rising Property Values

Don’t use the word “gentrification” to describe what’s happening in Capitol Hill.

Yes, property values are rising. Crime is down, vacant properties are being restored into multimillion-dollar housing projects, and there’s a new buzz on the area. Suburbanites fed on a heavy diet of urban-romantic sitcoms are flocking back because suddenly red-brick houses are cool.

Capitol Hill is a long way from the real- estate bust of the 1990s, the crack epidemic of the mid-1980s, or the halcyon “Burn, baby, burn” of the late 1960s.

But use the G-word to describe the housing trend on Capitol Hill and people’ll get their hackles up.

“Here in Washington, it has come to mean displacement,” said Monte Edwards, an Eastern Market neighborhood activist. “Gentrification, before I came to Washington, had favorable meaning. It was trying to make the society a little more gentle.”

But, according to Marguerite Spencer, a senior researcher at the Institute on Race & Poverty at the University of Minnesota Law School, “The problem is that we often associate safety with whiteness and lack of safety with blackness.”

In her view, gentrification — i.e., an influx of new, affluent neighbors who drive up property values — is a race issue, and always results in poor communities of color being displaced.

As Institute on Race & Poverty founder John Powell said, “We do a wink and a nod, ‘We didn’t know this was going to happen.’ Certainly we knew it was going to happen.”

Exactly what is happening in the housing market on Capitol Hill right now is open to debate.

Don Denton, a veteran Capitol Hill real estate broker, estimates the average Hill house costs $400,000, double the price five years ago. He adds that 1,500 rental units have disappeared from Capitol Hill as owner occupancy has risen.

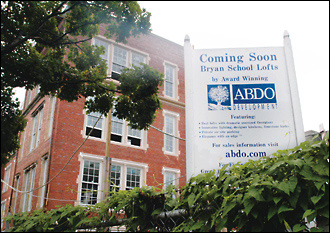

Jim Abdo, a building developer, is turning a dilapidated, empty old school into condos — and selling the penthouse units for $1.2 million. He envisions “successful lobbyists, attorneys, dual-income gay couples, young up-and-coming business people” as his future buyers.

But Jennifer Smolka, a Capitol Hill resident and Senate worker, is thinking of moving back to the Virginia suburbs she wanted to escape from a decade ago. Her car was stolen and she was mugged not long ago. “I’m thinking that I’ve dealt with enough,” she said, although she added, “The neighborhood is much better than it was 10 years ago.”

Joseph Fengler, a Hill staffer and an Advisory Neighborhood commissioner, said he was mugged, too. “I was at the [Capital] Children’s Museum less than two years ago and I was mugged by two gentlemen, beaten and sent to the hospital,” he said. But he’s not moving — and says talk of people being forced to leave Capitol Hill by rising property values is untrue.

“There’s a lot of great affordable housing,” he said.

For one thing, expensive housing projects on the Hill are the exception, not the rule. The Hill is a low-density zoning area with few empty lots or industrial warehouses ripe for conversion. Most of Capitol Hill is built up — and a sizable chunk of it is protected by a historical district designation. When people emerge from the Metro station at Eastern Market, “all you see is blue sky,” said Ken Golding, a principal at Stanton Development Corp. According to him, what makes the Hill real estate market significant is “that it hasn’t been significantly gentrified like the others.”

So is Capitol Hill gentrifying? A District spokesman said it depends on what part of Capitol Hill you’re talking about.

“There are pockets in Capitol Hill that tend to be very expensive and pockets of Capitol Hill where the houses tend to be more affordable,” said Chris Bender, of the D.C. office of the deputy mayor for planning and economic development.

Are poor people being driven out of the newly more expensive areas? “There’s cases all over the city where people have just found that living here may not be as affordable as it used to be,” Bender said, describing the displacement situation in Capitol Hill as “about average” in the revitalized District of Columbia.

Richard Layman, a Hill neighborhood activist, knows his neighborhood is changing, but said changes in the racial composition of his area aren’t due to rising property values. Even though in his neighborhood there are “more and more white people,” Layman said the overall population is D.C. is decreasing — describing the trend as one of blacks leaving the city and whites moving in.

But Powell said according to the data he’s examined, “Poor people of color in Capitol Hill are being pushed out.

“When you disproportionally push out low-income people, the vast majority of people who are affected by that are people of color, and that becomes a race issue,” he said.

At the same time, Powell allowed, increased interest in living and renovating Capitol Hill is a good thing. Fengler, the neighborhood commissioner, agrees. “As houses that were once boarded up become unboarded, renovated, sold and occupied, that helps the neighborhood grow,” he said. If in the process property values, and thus property taxes, go up, well, that’s the logic of the market. “You can’t artificially stop prices from rising,” he said.

Powell disagreed. “The housing market is probably the most regulated market in the United States,” he said, arguing that policies of gentrification mitigation are needed.

Don Rypkema, a downtown economic development consultant, said the first step to solving the conundrum of rising property values and displacement is discarding the very word “gentrification.” “The word itself has become so loaded, it just precludes rational discussion,” he said. From a logical perspective, he said, “You want property values going up,” because “if we’re going to take care of the least fortunate amongst us, we’re going to need tax revenues to do that.” Allowances for affordable housing need to be made in advance, he said.

Bender, the planning and economic development spokesman, said the District government has programs in place. There are incentives for first-time homebuyers, he said. “A new buyer could mean current renter,” he said. There’s a program in which the District takes “control of properties that are rather run down, vacant or abandoned. We sell them off to private developers, who have to rebuild and sell at usually below-market rates.”

Spencer, from the University of Minnesota Institute on Race & Poverty, said more drastic measures are needed. She argued for rent control.

All sides agree that Capitol Hill needs improvement. “I don’t think that it’s a bad thing that middle-class whites want to move back to D.C.,” Powell said. “Cities need a stable middle class, but it should not be at the expense of low-income people, low-income people of color, particularly,” he said.